■ disability law clinic

With a bachelor of arts in political science he earned from Wayne State in 2004, Binno naturally found himself preparing for the Law School Admission Test (LSAT). But he grew increasingly frustrated with his results.

“No matter how long I studied,” says Binno, “I couldn’t pass the logic games section.”

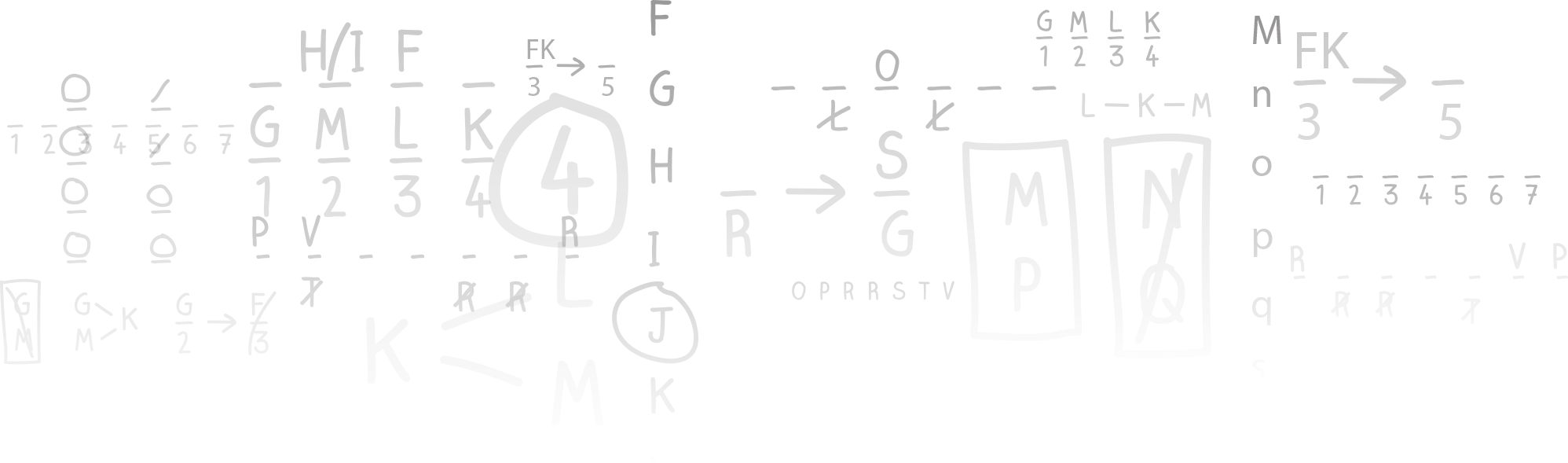

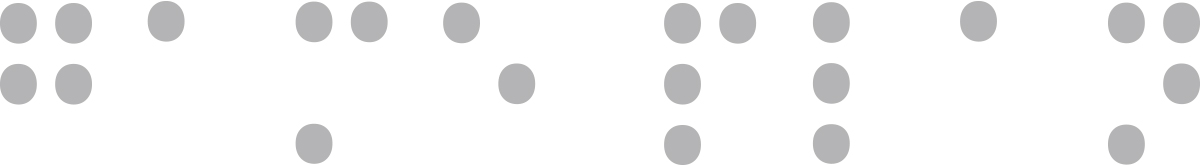

That section — also referred to as the analytical reasoning portion of the LSAT, which is one of four sections used in computing the test score — is comprised of word problems that, in most cases, are solved only after the test taker creates a picture.

“When you draw a diagram, you input the information that’s given to you,” says David Moss, associate professor (clinical) and director of the Disability Law Clinic at the Law School. “Then, through a logical reasoning process, you see inferences that you couldn’t have made intellectually through pure reason alone.”

But for Binno, who was born blind, drawing is a nearly impossible task. And, as Moss observes, the ability to create an image for the test should not be a barrier to entry for law school.

“If you’re going to offer an admission test for higher education purposes, the test has to actually measure what it purports to measure,” he says, citing the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA), a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination against those with disabilities.

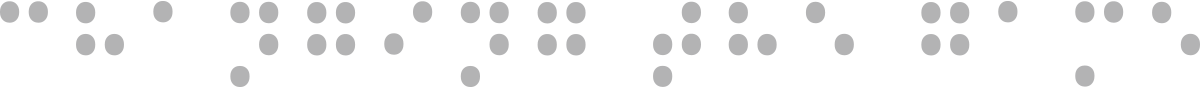

“Originally, the case against the ABA was very simple,” says Turkish, who is now president and managing partner of Nyman Turkish PC, a national litigation and disability law firm. “It said that if you require U.S. law schools to administer this test, then you essentially offer a discriminatory exam within the meaning of the Americans with Disabilities Act. What the ADA says is that it’s illegal to offer a discriminatory exam, and the ABA defended the suit by arguing, ‘We don’t offer it; we just require it.’”

Arguing that that was a meaningless distinction, Turkish — who became lead counsel after Bernstein was elected as a Michigan Supreme Court justice in 2014 — took Binno’s case against the ABA through the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Cincinnati. Turkish, who is also legally blind, says he’ll never forget the moment that Binno’s father broke down in tears while leaving that courtroom.

“After the oral argument, I had a sense that the panel was against us,” he recalls of the 2-1 decision against Binno.

But that wasn’t why Binno’s father was emotional.

“He couldn’t believe that Angelo had the opportunity to bring a case like this because he was born in Iraq and immigrated to this country, and it’s unfathomable [to him] that Angelo could bring a case like this and get heard,” Turkish recalls. “And I said, ‘I’m not going to ever stop believing that Angelo can be an attorney and that he can succeed in law school and the legal profession. As long as Angelo wants to continue, I’ll continue.’”

After the U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari, Binno’s legal team went back to the drawing board. Turkish kept that 2-1 ruling in Cincinnati in mind, remembering that the majority argued that the ABA is not the party that writes the LSAT.

The Law School Admission Council (LSAC) does, though. And Binno was on board to hold it accountable.

“I knew it would be a very resource-intensive case,” he says. And that’s in large part due to Binno.

“When I first started this case, I didn’t want a settlement reached just for myself,” says Binno. “I wanted the system to change for all blind and disabled people. I want more blind and disabled lawyers in the field, and the most important thing to me was a change for everyone.”

Binno v. LSAC was filed in May 2017 and assigned to U.S. District Judge Sean F. Cox. In December of that year, another prospective law student joined the case.

Shelesha Taylor, who also has significant near-point visual impairment, filed a motion to intervene as a party to the lawsuit. As a proposed plaintiff intervener, Taylor — a disability rights advocate from Virginia — presented yet another compelling argument against the logic games section.

The scope of Binno v. LSAC made the case all the more exciting for students in the Disability Law Clinic, which Moss launched shortly after joining Wayne State University’s faculty in 1998.

“We tend to get involved in cases where the stakes are significant to the individuals involved, but not to the world,” Moss says of the in-house clinic, which handles a mix of cases ranging from those that center on access to assistive technology (think speech-generating devices and power wheelchairs) to disability civil rights and Social Security Disability Insurance.

But the stakes were indeed higher with Binno v. LSAC, which had added excitement with its focus on the LSAT — an exam with which Wayne Law students are quite familiar.

“Certainly, the fact that the issue in this case related to admission to law school was something that instantly every student in the clinic knew a lot about,” says Moss. “They knew exactly what we were talking about when we were talking about the logic games section of the test, and understanding what’s involved in taking and preparing for the LSAT — how important the LSAT is to your ability to get into any law school, let alone get into the law school you want to go to.

“It’s not that cases that don’t have those features aren’t good teaching cases,” he continues, “but this was gold. Pure gold.”

“The case had been going on for a very long time before we got it,” says Dreher. “It was really exciting because we knew it would have an impact on a lot of different people.”

In preparation for settlement negotiations, the duo focused on researching their clients and educating themselves on what had already been litigated. Armstrong, who already had experience with litigation and pre-litigation, was eager to focus on the later stages of a lawsuit.

Adds Dreher, “We were getting drafts of the settlement agreement — and it was our responsibility to go over the settlement agreement and make sure nothing was not in line with what we had discussed — and we had to make it understandable to our clients.”

Moss suspected that Binno v. LSAC would be a key learning experience for his students.

“Working with a blind client and getting to know them, I think it really changed how students think about disability and the impact of this,” he says. “There’s no reason why blind individuals can’t succeed in law school and in the practice of law.”

For Turkish, who earned his J.D. from Northwestern University in 2012, working with students from the Disability Law Clinic was a gratifying experience.

“Law school wasn’t that far away from me,” he says. “Experiential learning in law school was really important, and I was thrilled about having law students join. They were doing highly substantive work on this case.”

Turkish vividly remembers working with Wayne Law students on depositions in Philadelphia. “I sat in LSAC’s boardroom,” Turkish says, “and I said to myself, ‘This is going to help resolve this case because this is an absolute embarrassment to this organization.’ Here they are, promoting access to a legal education and so forth, and here we are watching students take their deposition on their systematic discrimination against the blind.”

He continues, “I think having law students prosecute this case against the LSAC hit pretty close to home.”

Binno, too, was eager to work with Wayne Law students. “The students were amazing,” he says. “They showed passion for my case and really took an interest in helping me change the system.”

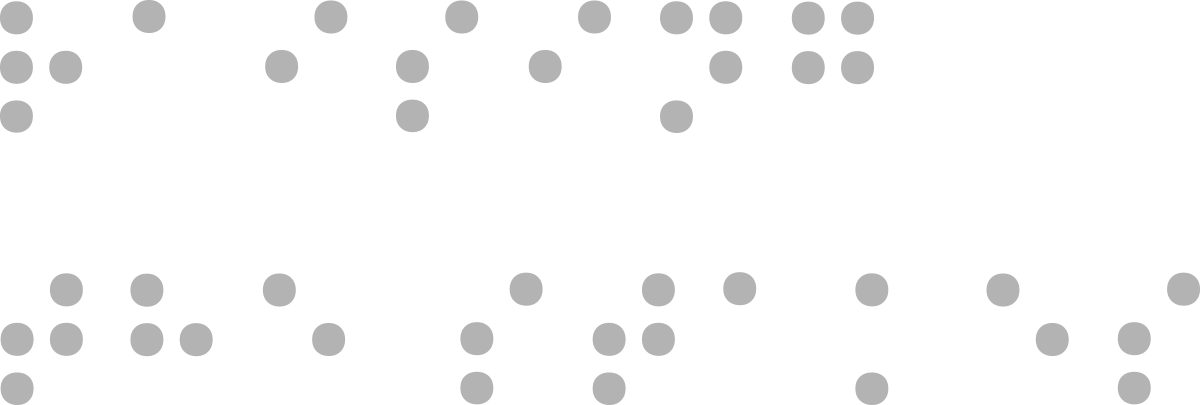

Although many terms are confidential, a joint press release was issued stating that the Law School Admission Council has begun research and development into alternative ways to assess analytical reasoning skills as part of a broader review of all question types to determine how the fundamental skills for success in law school can be reliably assessed in ways that offer improved accessibility for all test takers. Consistent with the parties’ agreement, the council will complete this work within the next four years, which will enable all prospective law school students to take an exam administered by the LSAC that does not have the current logic games section but continues to assess analytical reasoning abilities.

“This is, unfortunately, not an overnight process,” says Turkish, noting that the LSAC will “double down” on its efforts to provide reasonable accommodations in the interim to help prospective law students complete the logic games section. And ultimately, all prospective law students will benefit from the changes to the exam.

“Everyone will be able to take a test that doesn’t have the current logic games section, and that’s because of Angelo and Shelesha, and maybe a small part because of David and me — and no small part because of the students at Wayne State.”

What’s more, says Turkish, “Whoever sits on the U.S. Supreme Court in 30 or 40 years is going to take a different test to get to law school because of what those students did.”

Today, Binno is more determined than ever to attend law school. “I’m reaching out to law schools and telling them about my case and the difference I’ve made,” he says of his nine-year fight for justice. “And I’m hoping one of them will accept me.”

Turkish, who has represented Binno his entire legal career, is similarly resolute. He says that he’ll think about that 2-1 ruling in Cincinnati for as long as he’s practicing.

“Out of defeat from the ABA case, we ended up with a much broader victory, and we instead have a system where you’ll be able to apply to any law school with a test that you can fairly compete on,” he says. “The road was longer, but the victory was better.”